The central discussion focussed on:

- Whether the text should reference ‘domestic’ dispute resolution mechanisms, with country delegates expressing concern that the term may limit the flexibility needed to resolve tax disputes and in turn create confusion. An alternative suggestion was to use a more neutral term such as ‘appropriate’ mechanisms. There were also repeated calls for clearer definitions of the types of disputes that Article 10 is intended to cover.

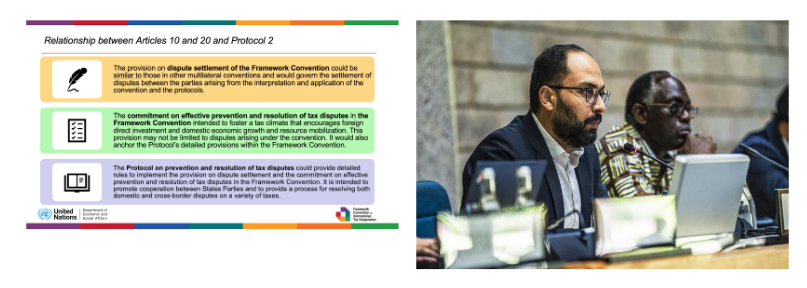

- The Relationship between Articles 10 on Prevention and Resolution of Tax Disputes , 20 on Settlement of Disputes arising under the Convention, and Protocol 2 on the Prevention and Resolution of Tax Disputes.

Image 1 derived from Workstream 1 on the Prevention and Resolution on Tax Disputes | Image 2 Photo of Ramy Yousef, Chairman of the Negotiating Committee – Photo by IISD/ ENB | Danny Skilton

The chair, Ramy Youseff, underscored that Article 10 intentionally leaves room for the Conference of Parties (COP) to develop guidance and outline examples of best practices associated with the prevention and resolution of tax disputes. Several delegations, including but not limited to Norway and Germany, supported the idea of maintaining a space between domestic and international approaches to this matter, while others, including the African Union, emphasized the need for a more structured and clearly scoped dispute resolution framework. Other delegations noted that Article 10 would eventually need to be read together with the broader dispute settlement provisions planned under Article 20.

Delegations also drew connections to related articles and global processes. Some linked the conversation to ongoing statistical work on illicit financial flows, underscoring the importance of clarity across the Convention. Others recommended distinguishing tax avoidance from tax evasion through a dedicated provision, to ensure conceptual precision. There were also proposals encouraging the publication of dispute-related decisions as a way to promote transparency, learning, and consistency across jurisdictions.

Civil Society Interventions

Civil society organisations stressed the importance of preventing disputes before they arise. They noted that early engagement, transparency, and accessible procedures are not only more equitable but also significantly reduce financial and administrative costs for countries. Their interventions underscored the need for a preventive, rather than reactive, dispute architecture.

Following a submission from June Cynthia Okello from the Pan-African Lawyers Union (PALU), she emphasized that, in the UN Tax Convention negotiations, preventing tax disputes is just as important as resolving them. She called for clarity, transparency, cooperation, and good faith to reduce the likelihood of disputes, especially because developing countries often lack the resources for long, complex tax battles. She highlighted that effective information exchange, public country-by-country reporting, and simplifying complex tax principles (such as the arm’s length principle) are key to preventing disputes. The statement also notes that many cross-border disputes originate from transfer pricing, showing why clearer and more balanced rules are needed. Overall, her intervention played an integral role in urging negotiators to build an inclusive, fair, transparent, and efficient international tax system that strengthens the legitimacy and fairness of global tax rules.

June Cynthia Okelo, Pan African Lawyers Union (PALU) – Photo by IISD/ ENB | Danny Skilton

A second submission from Mr. Robert Mwale from Center for Trade Policy and Development (CTPD), raised concerns that Article 10 is unclear and overlaps with Article 20 and Protocol 2, making it uncertain what kinds of disputes it covers, between which parties, and on what legal basis. He argued that Article 10 should focus primarily on preventing tax disputes, through stronger cooperation and greater transparency measures such as automatic exchange of information, public beneficial ownership registers, and country-by-country reporting. While acknowledging the need for dispute resolution, his intervention warned against introducing arbitration-style mechanisms, noting that similar systems in other international frameworks have been costly, opaque, and restrictive for developing countries. Such mechanisms often drain public resources and weaken policy space.

Robert Mwale, Center for Trade Policy and Development (CTPD) – Photo by IISD/ ENB | Danny Skilton

The recommendation is that Article 10 should be limited to dispute prevention, while all dispute resolution procedures should be handled under Article 20, ensuring a clear, fair, transparent, and sovereignty-respecting approach. Overall, the intervention calls for Article 10 to reinforce cooperation and prevention, not to open the door to parallel arbitration systems that could disadvantage developing countries.

Introduction of Article 11 on Capacity Building and Technical Assistance to the Negotiations

The Chair introduced initial ideas for Article 11 and invited views on whether support mechanisms should be consolidated into a single dedicated article or integrated across different parts of the Convention. Several delegations emphasized that a stand-alone article is essential for effective implementation and should provide comprehensive, well-structured support. There was broad acknowledgement that many countries, particularly those with limited institutional and human-resource capacity, including small island developing states and least developed counties, would greatly benefit from robust technical assistance and capacity-building frameworks to ensure they can fully participate in and implement the convention.

Photos of the Outside Area at the United Nations. Photo by IISD/ ENB | Danny Skilton

Stay tuned for more updates as we continue to negotiate for a UN Tax Convention.